“You are not to muzzle an ox when it is treading out the grain.”

-Deuteronomy 25:4

The law we encounter next is an interesting one.

We’re told to NOT muzzle an ox while it is out in the field threshing the grain.

While from one perspective this may seem like the most logical and humane thing to do, from another perspective (especially in the Biblical era), not muzzling an ox while performing it was its duty as a beast of burden was one of the most unproductive actions you could take.

The truth is if one ever hoped to get the threshing in the field completed within a reasonable amount of time, not only did the ox have to be muzzled but the beast had to be whipped so as to keep it working.

Let’s take a good look at the logistics of the situation here.

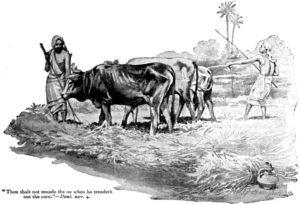

How the threshing process worked is that the ox would pull a sled or threshing skid over the top of the grain stalks to get the ripened kernels to separate from the heads.

Or…

…the ox would directly trample on top of the stalks of grain to achieve the same effect.

Now here’s the productivity problem that results when we don’t muzzle an ox.

Oxen are essentially grazers by nature.

In other words, when they’re out in the field they just loooooove to bend their necks down and constantly eat during the threshing process…kind of like me with a bag of sour cream and onion flavored potato chips.

Unless you muzzle me, I’m gonna finish the whole bag in a short couple of minutes.

So we can see from a purely practical perspective, if a farmer wanted to get the threshing done in minimum time with as much minimum effort as possible, it was to his advantage to muzzle his ox.

If he didn’t, he would have to constantly whip and goad his ox to keep it moving.

And that would actually seem to defeat the purpose of Deuteronomy 25:4 which is to show compassion to the animal.

Yet the Torah tells us in plain black-and-white language that you are NOT to muzzle your ox.

So what to do?

Well, according to the records, the Hebrews implemented a balanced compromise.

They would actually keep their oxen muzzled but would also occasionally remove the mouth guard so their animals could eat.

This would achieve the effect of being in harmony with the spirit of the command to treat the beast in a humane manner and also achieve a level of efficiency sufficient enough to get the threshing work accomplished in a timely manner.

The next time we meet, I’m going to show you how the principle of not muzzling an ox was brought forward into the New Testament in a unique context.

This is absolutely fascinating.

Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply